by futurist Richard Worzel, C.F.A.

With all the (valid) concern about the rapid onset of climate change, most people who comment on and study climate change are overlooking what may be the single biggest driver of climate change in the future: human population growth.

One of the arguments that I get most frequently from people who want to deny climate change, for whatever reason, is “Nature is so big, there’s no way we could affect it.” This wasn’t true even when human population was a small fraction of what it is today. Humans have hunted large animals to extinction for thousands of years, changing the ecosphere around us. As one researcher put it, whenever humans and their ancestors are around, large animals tend to disappear.[1]And now the same is true with respect to climate change.

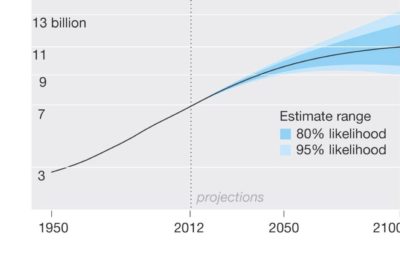

According to the United Nations, it took all of human history up to the beginning of the 20thCentury for human population to grow to 1.6 billion. By the end of the 20thCentury, population had exploded to 6.1 billion.

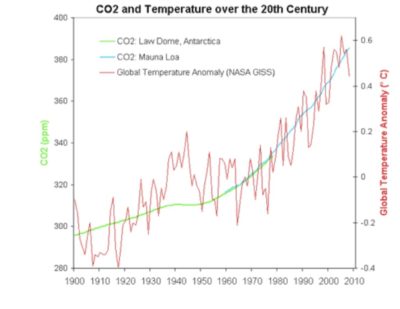

Over the same period, carbon dioxide concentration in the Earth’s atmosphere went from approximately 297 parts per million (ppm) to about 375 ppm, largely due to the Industrial Revolution, and the increase of human energy use. The so-called Greenhouse Effect of CO2is well documented, with the result that Earth’s temperature has risen significantly as well:[2]

Chart I

This is well documented, well established, and accepted by anyone who is honest about climate research. But that’s the past. What about the future?

Well, again, according to the United Nations, global population has expanded from 6.5 billion at the start of 2001 to more than 7.7 billion by the end of 2018. It’s projected to reach something like 9.8 billion by 2050, and reach on the order of 11.2 billion by 2100[3].

Chart II

The Implications for Climate Change

So, what does this imply for Greenhouse Gas (GHGs) emissions and climate change? It’s a huge, unwieldy question, but let’s take a shot at it using very rough, back-of-the-envelope estimates.

According to the Phys.org website, total carbon emissions in 2018 were 37.1 billion metric tonnes (a metric tonne is 1,000 kilograms, or about 2,200 pounds). With a global population of 7.7 billion people, that averages out to roughly 4.8 tonnes of CO2 per person per year.

That is, of course, a gross oversimplification. The average American produces a lot more CO2 than the average resident of sub-Sahara Africa, and there are more Africans being born than Americans.

But I said this was a rough calculation, just to get a sense of what growing population will do, so let’s just run with it.

By 2050, an additional 2.1 billion people would throw an additional 10 billion tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere annually, for a total of 47 tonnes per year. By 2100, an additional 16.8 billion tonnes of CO2 would go into the air every year, for a total of 53.9 billion tonnes per year.

Anyone who’s been paying attention knows that there’s a lot of discussion about reducing emissions. For the moment, let’s just see what it would take to keep dumping only 37.1 billion tonnes of CO2 per year.

If, by 2050, which is 21 years away, there were 9.8 billion people dumping 37.1 billion tonnes of CO2, then each person would, on average, be responsible for only 3.8 tonnes of CO2 per year – a decrease of 21.1% from today’s rate. A quick peek at Chart I above indicates that this would be a dramatic change in behavior, one without precedent in human history, which has seen energy use climb, and GHG emissions, climb relentlessly as population and living standards have risen.

It’s possible we might accomplish this feat, but it will take a massive change in behavior, and not just by those who understand how important it is, but by everyone. Moreover, people in developing countries are going to want to know why they should reduce their expectations of a better life while people in rich countries continue to enjoy their much higher standard or living.

I’ve maintained for more than 20 years that the only way to get the process of reducing emissions started is for us to find new ways of doing things that make it more expensive to emit GHGs than not to emit them – in other words, for it to be profitable to be responsible. And the overly simplistic analysis that I’ve produced above, does, I think, underline that belief. I don’t see any other way of getting enough people to change the way they live.

Some of the Problems with This Analysis

I’ve said this is overly simplistic, so let me at least acknowledge the ways that my approach is inadequate.

First, I’ve dealt with just one variable in the whole equation, population. I’ve mentioned, in passing, that standard of living is important, as is the efficiency of energy use (more efficient means less pollution, hence less GHG). For a more complete analysis of these, and related variables, read something like Patrick Brown’s analysis here.[4]

But wait, there’s more! More people require more housing, which typically happens by clearing and paving over forests or farmland. This reduces the amount of carbon absorbed by the biosphere, which increases the amount of GHGs in the air. And more people eat more food, and higher standards of living lead to greater consumption of both meat and milk. This implies more food animals, which produces more waste, and requires more energy – all of which increases the amount of GHGs in the atmosphere.

It’s clear, then, the increasing population increases potential GHGs at faster, and potentially much faster, than population growth.

Where Does That Leave Us?

If we don’t or can’t do that, then population growth will overwhelm any and all efforts to reduce carbon emissions – and condemn us to temperature increases that shoot well beyond the 2o Celsius that climate scientists believe is critical to the well-being, or even survival, of human beings, as well as many of the other species on Earth.

Accordingly, it’s my belief that the single most important thing we can do for the well-being of our race, and the Earth’s biosphere, is to reduce the rate of growth of human population as quickly as possible.

This is a topic that has been well researched, and there are several ways of doing this that are notably successful, but two in particular.

The first is to educate girls and women, particularly, but not exclusively, about contraception. This gives them a much greater awareness of how and why babies are conceived, and enables them to take steps to reduce the number of children they bear, and produces significant drops in family size. Of course, this runs counter to the cultures in some societies, particularly those where the status of men is tied to the size of their families. But it does tell us what we need to do to take this most effective step towards reducing population growth.

The second thing we can do to reduce population growth is to increase the standard of living of people in developing countries. Among poor people, having large families is the closest thing they can get to a pension plan. And in agrarian societies, large families represent cheap labor.

Of course, higher standards of living are closely linked to energy use, which is closely linked (so far) to GHG emissions, so this is very much a two-edged sword. Still, it means we need to invest time, effort, resources, and thought into how to lift people out of poverty in such a way that they benefit, but don’t add to the carbon burden in the atmosphere.

But the bottom line is clear: We have an enormous task ahead of us if we are to stave off ecological disaster, but perhaps the single most overlooked thing we can do is to work hard at reducing population growth. To do otherwise will negate most of our other efforts are limiting the increases in global temperatures.

© Copyright, IF Research, January 2019.

[1]Yong, Ed, “In a Few Centuries, Cows Could Be the Largest Land Animals Left”, April, 2018, The Atlantic, https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/04/in-a-few-centuries-cows-could-be-the-largest-land-animals-left/558323/

[2]Cook, John, “CO2/Temperature correlation over the 20thCentury”, Skeptical Science website, 18 June 2009, https://www.skepticalscience.com/The-CO2-Temperature-correlation-over-the-20th-Century.html

[3]https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/world-population-prospects-2017.html

[4]https://patricktbrown.org/2017/09/15/the-effect-of-population-growth-on-climate-change-impacts/